Syafiatudina (Dina): In Indonesia OTB, Organisasi Tanpa Bentuk, or organisations without a form, was a term used by the Government during the Suharto regime as a name for a group of people who were conducting illegal or illicit activities related to Communism or other forbidden ideologies. These were unregistered so they didn’t have a legal status.

In the late 1990s to 2000s many art and other organisations started registering themselves as legal organisations and started to adapt formal structures, such as with a director, a manager, an accountant, a board as required by the government. We have been talking about how these positions or these job titles affect how these collectives or groups of people operate––that’s also how we decided to name this conversation. Before it was quite horizontal, everyone chips in, in a way that they believe in, and contribute however they can. But after the legalisation what happened, or changed, what didn’t change and what is still happening?

For example, Antariksa mentioned the expression hanya di atas kertas, or “only on paper.” On paper there is a Director, there is a Manager, but in the reality of daily practice, they are still collective and fluid. But is this really fluid? There is a tension between structure and non-structure in organisations.

Emily: I started working at The Showroom in 2008 and before that I was at Casco from 2005-2008. In both cases I arrived at a point when the organisations needed some restructuring and rebuilding. I had to move both to new spaces, which also involved developing their programmes, audiences and also their economies and building networks for them in order to strengthen them. Both organisations felt quite vulnerable, and perhaps still are. This got me interested in how as a director your perspective is on the organisation as a whole, which means thinking about the structure in relation to what you’re producing, and how the projects and ideas become quite embedded in how you work.

I’ve not been working on this alone as when I moved to The Showroom and Binna took over my position at Casco, we decided that we would continue to work together. Over the last five years we have collaborated on two programmes––Circular Facts and Cluster––which were funded by the European Union. Through this, there has been a loose ongoing exchange between our organisations over a period of six years, which has not only been about producing projects, but about how we produce and the structures that are needed in order to do this.

Binna: Over last week, we have visited and been having conversations at various organisations, including Forum Lenteng and ruangrupa in Jakarta, and Lifepatch and Teater Garasi in Yogyakrta, and KUNCI of course. The focus of our conversations was “how” they are organising in terms of their organisational structure, physical space, finance and process of working, while they are programming, whereas the usual approach to an organisation is just to hear about the program, the visible result.

We aimed to gain insight into shifting organisational structures, the economy and relations and also probably conflicts within these and then how this interacts with their programmes. I think this interest comes from various experiences and one, which Emily mentioned, is the Cluster network which is a network of eight organisations ranging from a museum just outside of Madrid, to spaces like us and Tensta Konsthall (Sweden), and the Israeli Centre for Digital Arts in Holon. We all operate quite differently from any other museum practices and most of us are located in residential areas and on the “periphery,” so we started asking how we are different, what actually we are doing differently from others, and what our values are.

Emily: One of the things we as Cluster did was to visit each other to get to know each other’s work, which included walking around each other’s neighbourhoods as well as what was inside the organisations, and looking at how each is constituted through the relations with our environments and what this can produce in terms of an organisational environment.

Binna: One of the commonalities amongst these organisations’ situations is what you might call “community works”: working with a community of concern, and community, or a place nearby, is a very important factor. This kind of practice, although it could be easily co-opted, is something that is not always valued by the cultural policies of the countries in Europe where we are, and that’s part of the thing that brought us together in 2008. The Global Financial Crisis that affected many countries in Europe had a knock on effect of funding cuts. Organisations like us are the best target of those cuts because we are in between art and social practice, our identities in terms of “art” aren’t clear and so… By working together, we not only secured certain financial supports for our programme, but our position in the field as well. The Showroom and Casco informally became sister organisations, sharing practices.

Speaking about that, we never labeled this as such, but feminism is a very important struggle, theory and practice that shapes us, and our work, and relates to this interest in organisational matter. One could compare an organisation to a house and a household, where mostly mothers are still in charge and those ‘jobs’ are rarely made visible and not considered to be public work, just something that enables public work. The gap could be even more intense in our type of practice. So I think another reason for this investigation is to have a feminist reading and validation of the work that we do, this against the capitalist mode of validation. But when we were at Bumi Pemuda Rahayu (BPR) two days ago, there was a sense that we’d better not talk about “capitalism.” (laugh)

Antariksa: More or less, yes. I think most people there didn’t really want to talk about capitalism in an abstract way.

Binna: But I have to say, I think capitalism––patriarchal in nature––is really infiltrating everywhere, so we are really thinking and acting through the idiom of this. Only seeing and thinking of the product belongs to that. If our organisations are working for an alternative to such rule of capitalism, I think it’s important to speak of the language and mode of our organisational practice, I would say, as part of anti-capitalist struggle. That’s why we have begun this research, and a series of meetings at various organisations last week, which was very inspiring!

Antariksa: So we want to know the result?

Emily: Well the aim was not to have a concrete result. The reason we titled this event Curating Organisations (Without Form) is about this tension between structured and informal ways of working.

In my position at The Showroom I have to organise in a structured way, but at the same time I also have to make room for openness, for things to take their own course and have their own life. I worked in a bigger institution in the UK where the structure was so rigid that everything had to fit into it and there was no room for anything to be responsive, or for feedback to occur between the organisation and what it was producing.

Here in Indonesia it has been interesting to see how and where these kinds of tensions occur, if at all. Many of the organisations we met seem to have evolved through friendship and have then become more formalised at certain points, often in order to accept funding. A lot of that funding comes from outside, so I’m interested in how you continue to do what you do without having to respond to outside agendas.

In the UK, there is language and structures that you then have to take on to gain and sustain your funding. With the group Common Practice, The Showroom has been developing a critical approach towards these and an ambition to develop our own language in order to talk about value differently. Funders always want to measure what you do and assign value to it, so we are keen to create our own view of the value we are producing.

I was talking to Antariksa about the relationships between organisations and funders and he was saying that KUNCI is not dependent on them, that you would do what you do anyway without those funding opportunities, and it seems that this is the same with Lifepatch, who seem to have resisted going down the route of seeking funding so that they wouldn’t have to respond to outside agendas.

Binna: Teater Garasi even decided to re-informalise and downsize, which includes get riding of their salary system and making the majority of members part-time.

Emily: Forum Lenteng talked about how to enter into the political domain and start to influence from within. Hafiz (Rancajale) has been working with the Arts Council, as is Ade (Darmawan) of ruangrupa, and they wrote a policy proposal. Certainly what kept coming up is how do you relate to the outside, and how do you keep doing what you do without compromise? It’s the same kind of question that we are faced with in the UK where there has been a big shift towards the privatization of culture, so all the arts organisations are under pressure to solicit funds from private sources, which creates a situation where you have to adjust the way you do things. There comes a point where you start to question, how far you have to go with this.

Ferdianyah Thajib (Ferdi): What interested me from our last conversation is when you asked us how we do our daily conduct, and also when you shared what happens in your own organisational practice, a lot of it had more affective aspects to it and its unaccountable––almost unaccountable. This kind of investment friendship and passion for work and producing what we are producing is something that is not actually thought of by funding bodies as valuable, where as we are actually creating values not just among ourselves as organisations but also with the communities that we are engaging with. But we always seem to fail to translate that into quantitative terms. I don’t know how Hafiz would do it when he wants to approach policy or if any structure would be able to value these other kinds of values, immaterial values.

Emily: In fact, for the Common Practice conference we are holding next week, we will shift our focus from value to values, and how to hold these at the center of our work. This is something that links the three organisations represented here today. We are all working with very diverse communities, but it’s happening in an intimate way through long-term engagements, which is difficult to assign a value to. The communities range from the Researchers’ Affects team who are in residence here [at KUNCI] this week, students that come here and engage with the organisation, and the communities who you work with in the kampongs.

It’s the same with The Showroom, on one hand we are bringing in academics, hosting PhD research groups and holding theoretical discussions, we also work with artists and students and with a wide range of local groups, then we are part of networks, such asCluster and Common Practice. These are all different communities that we are closely engaged with in ways that are long-term and open ended. Once we have finished a project we often don’t just move on. Once a relationship is formed you can actually do more because you trust each other, you have a friendship, you can understand each other’s needs and desires and where something productive can take place.

Binna: Our experience at Casco could be useful too. Around 2011/12 under the threat of the general budget cut in the cultural sector in the Netherlands, Casco’s Board at that time thought that we needed to strengthen our financial capacity and that we needed to hire a financial manager, or a fundraiser, just as in many other companies and organisations, which creates a further hierarchy. They were also rigid about pre-existing job descriptions, their divisions, and the contract matters in the name of professionalization. But in fact, these were the last things that we needed. Our small team believed that we needed people who could work together on the content and share certain values together, which functions as a fundamental basis for generating necessary money. We had to struggle hard to keep this conviction into practice, which eventually resulted in the change of the whole board who did not support this idea. And this struggle was not possible without support of a community of friends. It was a worthy struggle as it turned out to be a breaking point for our organisation to grow externally and internally.

Lifepatch is another example to consider. There everyone of the group has particular skills that they bring, and its not like one person is in charge of PR and the other of fundraising, but everyone is doing something in relation to a project, and bringing their respective knowledge into what they do. The same goes for KUNCI. You went through this structural change where you decided to call everyone as a member. ruangrupa who now has more than 35 members, just went through the restructuring: Before they had a somewhat abstract, conceptual division of their work like Research and Development Division. Now they got rid of this kind division and structured the whole team around projects and a “coordinator” for each project, while they still keep the directorship and the board “on paper”. All of these show how professionalization or standardization is the way of truth: how informality that is inclusive of the affective aspect of an organisation is an important value to protect. And besides the articulation of this values as we do, I think we also should work in common, let’s say “organising” ourselves.

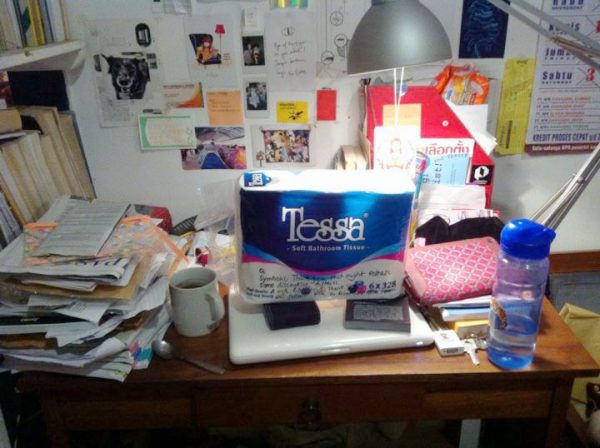

Dina: I will reflect on my experience at KUNCI. Two years ago Ferdi proposed to either to make us all Directors or make us all Members and the response was that we should be all Members and that everyone would be responsible for a project. So for this project I will be the project officer, someone will be the researcher, and on another project Antariksa will be the project officer and I will help maybe as a researcher. So I think this shift is an example of working collaboratively or ‘in commons’ where everyone supports each other. But in this very lose term of Member there is not really clear job divisions on how to run the space. For example, we are all members but does it mean we are all responsible for toilet tissue when it runs out? Or is everyone responsible for buying Cephas [KUNCI’s dog] food when it runs out? It’s already empty!

Ferdi: It’s your responsibility Dina! (Laugh)

Dina: No it’s Wowok’s.

Antariksa: Yes it’s in your contract Dina. (Laugh)

Dina: And then as I contemplate when I am in the supermarket buying toilet tissue, I wonder if we had someone specifically in charge of buying toilet tissue, buying Cephas’ food and checking that we still have water. We have a finance manager who pays the electricity and the internet bill, but if we had a person in charge of small errands for the domestic work, would I, as an intellectual, write more? Would I produce better quality projects because I have more time to think? Because I worry that if I start to think this way, then I will start to put domestic work or ‘mother’s’ work, it’s downsizing its quality, or potential for more engaging intellectual work or masculinity. Now I am interested in working with the mothers of this neighbourhood, but how will I approach the mothers if I see domestic work as a burden to my intellectual life? Maybe this is something outside of our conversation but I know that I’m not alone, for example Lifepatch are a collective but they are also living together, and how does this separation work between who produces the idea and who enables this idea to be produced come about there? Is it being separated or not? For example MES 56 also has a manager.

Wok The Rock (Wok): I feel guilty now. [Wok the Rock lives at KUNCI.] I feel like a parasite here. I don’t buy toilet paper, I don’t buy water, I just live here. I only pay rent and maybe lock the door at night, because I have to take care of another collective.

Binna: And there are you buying toilet paper for them?

Wok: Yeah!

Dina: We are in the same position for different spaces.

I don’t know if anyone wants to talk more about who produces the intellectual property and who enables this intellectual property to be produced by doing the domestic work in these sorts of organisations?

Emily: I think these things are intertwined. For example, I do a lot of management and fundraising and all sorts of things that are not where my main interests lie. But if you take it as a whole, you see how these things inform each other, without doing those things we wouldn’t be able to realize our programme, so the content and the structure are integrated and shape each other. If you separate off the menial tasks, you would be a different kind of intellectual to the one who is sometimes mopping the floor. You could see these things as part of an organisational practice. It is a way of thinking that is also particular to what we wanted to highlight when looking at these organisations.

In a large institution, everything is segregated. I worked at Tate and was a very specialised cog in a massive system, and have to network with all the other departments. The dynamics of multitasking to me is an interesting way to work. Your consciousness works in a different way, you’re aware that you have to buy loo roll and do this and that, so maybe your intellectual work does suffer with this split concentration, but I also think it produces a different kind of position, which is not un-valuable.

Edwina Brennan: This reminds me of my time in public institutions in Australia. On one of my first days in Sydney, when I was interning as a 19-year-old, I was so nervous and petrified and was in the staff kitchen where there were all these dirty plates and I thought I would be a good little intern and stack the dishwasher, this fancy pull out dishwasher. So I asked this really very hard-nosed curator how to turn the dishwasher on and she glared at me and replied “Can’t you ask somebody else who actually has time!” So the next person to come in to the kitchen was actually the cleaning lady so I asked her and she said “Oh you don’t need to worry about that, but you just press this button under here.” So it was one button, but this curator didn’t have time. I also thought afterwards that it was probably also code for the cranky curator not actually knowing how to turn the dishwasher on.

I think its interesting once you get deeper into those big institutions because you realize that no one actually knows what they are working for. There isn’t a common vision. So I really like what you said Binna about using the organisational structure to also define your values as an organisation and what you are actually working for. That’s really the worry of big institutions; nobody knows how their cogs fit together anymore.

Binna: Actually at Casco we have recently started cleaning together. So the picture we put on Facebook for this event is of our second session of cleaning together. Somewhere in the book Grand Domestic Revolution Handbook, there is reference that we took, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Maintenance Manifesto.

She did cleaning in front of museums as a series of performances and she wrote this manifesto for maintenance art where she contrasts maintenance to development. Where she did this cleaning performance alone, however, at Casco we did it together. And it was not only for symbolic representation: we had exactly that dilemma of who is cleaning and who is not. For example, two staff members were signing off an email to the rest of the team, sarcastically, with ‘Thank you, Your Lovely Housewife.” While working with domestic workers in the Netherlands, many of whom in fact come from Indonesia, in fact it’s a global structural problem that we can find in our houses and in our organisation as well. Hence, we decided to clean our office every Monday all together after our regular general meeting. At first we cleaned for an hour or even more. Then, as we do it every Monday, it does not take a long, and we set a rule not to do longer than 30 minutes. It’s manageable. Also what this brings is a kind of physical relation to our space, so we feel more ownership I guess, to use an economic term.

Emily: The Showroom also works with a domestic workers union in London (Justice for Domestic Workers), who lobby around immigration issues. One of them told me about how a politician complained to her about unskilled labour in relation to immigration, which upset her, she responded that domestic workers are highly skilled: “We can cook, we can clean, we can look after children, we can organise…” There is a different kind of value that they are campaigning for in order to shift the social perception of their work. I think that’s something that one can keep in one’s own consciousness in relation to what’s valuable use of time. Some of the work that is more about caring for things, like feeding the dog, is important to what this organisation is and does.

Antariksa: I have to admit that KUNCI wasn’t designed as a modern organisation. It was started, I think more from a circle of friendship. But I think I it happens everywhere in Indonesia, I don’t know if it also happens in Europe. But we started hanging out together, sharing ideas together and then, well why don’t we make this together. It was as easy as that. But then after one or two years, we thought to be able to become a proper research center, we needed to have a physical space, a library, an office, so all these ‘needs’ then also constructed our way of working. So we needed to have this new system, an inorganic system. We just followed this ‘new culture of organisation’. So you need to have budgets, annual planning, that kind of stuff and at the end of the year you need to have an annual report. Suddenly having this organisation became no longer fun.

It was very interesting when we had conversation with Teater Garasi, because now they define the notion of sustainability into two categories: sustainability of ideas and economic sustainability. So more often for us, when we think about sustainability, we think more into economic sustainability, how we can raise more and more money because we need to pay our bills every month, we need to rent a new house, we need to publish books, but we never were really thinking about sustainability of ideas. Sometimes when we negotiate, for example, with funding agencies, in most cases actually, they will also intervene in our ideas, so economically we became sustainable but they actually don’t really give a damn if our ideas will sustain themselves or not. As long as we can finish the report every year and we can send them beautiful photos and videos and publications––that’s it, its done.

So I was thinking how can we negotiate more with this original culture of organisations based on our own interests and how can we negotiate with the needs of funding agencies, lets say to develop a more ‘modern’ understanding of organisational practice or modern definition of sustainability, for example.

Based on our experience, again we registered as an organisation officially and we have, on this piece of paper this structure, Director, Manager, Finance Officer etc. and every single time when we should sign a contract, we should put at least one name of someone as Director of KUNCI Cultural Studies Center. Each time even though in fact, we don’t have a Director, we are all members. Its impossible to let them know that actually we don’t have this structure because then we will loose our opportunity to get this money. So it is really hard to find a way to negotiate this with funding agencies.

Emily: You talked about this progression, or evolution, from a group of friends exchanging ideas to having a space and then becoming more formalized, but also in that process you go beyond this and build a wider community. Then you start to have to take on a bit more responsibility because you are starting to become an important place within your locality, for the communities that we described earlier.

Binna: Well I think we should have, not in a progressive way but by occasion, a shift from organisation to organising. So what Hafiz told us about negotiation––I think he used the word negotiation almost in every sentence!––was that he and Ade together started organising this nationwide collective, the Artists Coalition, which brought them to the Jakarta Arts Council, which represented a great shift in Jakarta Arts Council policy. This gave them contact with the ministry and the ministry then asked them to write the policy paper. This move is very interesting and it is also similar to what we experienced at Casco when we had a crisis, a power of organising.

Ferdi: If I may beg to differ to what Antariksa was saying earlier. I actually see a cultural value or an organisational value at KUNCI that has existed from the beginning, which is our culture of ngeyel or resilience. Because we don’t use negotiation that much, or in a sense that Antariksa said that we are always reporting back [to the funding agencies] but still, we are always reporting back in the way we want it, in the time that we want it, whether the funding body is happy or not. If the funding body is knocking on our door asking for that report we still say “wait, we are still doing something else.” So that’s also a culture which sticks. Even the decision to not buy a piece of land for office building for instance, because we knew that once we bought a piece of land we would commit to something big, and we don’t even buy a piece of land for ourselves so why would we buy this piece of land for this institution? Because we know maybe one day the organisation will dissolve and we don’t want to be burdened by that. And I think that’s also important, this positioning that Emily was talking about. We are good at that, “not negotiating,” at the same time we are also good at putting forward what we think is important. Even when we got commissioned to do something, usually we say yes in the beginning, but it’s actually just for the beginning, later on we develop it to something that suits more to the process development. Of course at the end of the day, a compromise is still needed, like when they required us to submit a narrative report. But usually we use this opportunity to clarify why we modified certain things, the reasoning behind it, as we always see the need to adapt to unfolding processes. So for me it is not a matter of what is organic or inorganic anymore.

Emily: Maybe its just pragmatism. I wonder whether there is an issue of leadership––you don’t want to be leaders? You have this flat membership model, but actually if you have a space and have created this context, you also can’t avoid being leaders. Hafiz has been quite strategic in this respect, entering into policy, taking leadership in that system on behalf of others.

Edwina: Actually I wanted to ask a bit about the role of mentoring. There are sort of inbuilt social hierarchies in Indonesia, for example if Antariksa meets a senior from his university its always very polite, if one of Antariksa’s juniors from university it’s the same. While KUNCI is a lot flatter now, do you still think there is a form of hierarchy based on age and experience? I just wondered, you know, as a younger person seeking informal mentoring or as an older person and your responsibility to lead, I guess––going on from what Emily was saying about responsibility as well.

Dina: I think well, based on my experience in KUNCI there is never really a direct mentoring from KUNCI, they sort of push me to the hill.

Ferdi: Everyone is pushed.

Dina: Everyone has a specific skill and we believe that each person here has a specific skill or perspective that can enrich our being collective, or being together so in a sense its also quite horizontal. The tension, or the question of regeneration is also part of the discussion in many other organisations, but I have never felt there is a need for regeneration and I, with the younger generation, will continue this heritage.

Ferdi: There is an organisational age though, it matters when you started to join the organisation. I’m not saying what went on is kind of knowledge transfer, because we believe everyone has their own knowledge and then they bring that to the collective. But it’s more a transmission of awareness of what we are doing. That is something that is a bit tricky. Of course a lot of people come here just to hang out because this place is cool or whatever, but actually there is more to it than that, there is a kind of a shared value that ties us together.

Dina: I think I would like to add to what Ferdi had to say. It took me I guess two years to have the courage to say my opinion on what KUNCI is, and have my own voice about what KUNCI is doing. It’s not because there is often occasions for that, but it’s also the courage or knowledge of information that I received by being here a lot. That kind of awareness that is transmitted not in a very formal way or like a class about KUNCI history, but instead by making a coffee together or sitting here and talking about what KUNCI is, or even guests coming here and asking about KUNCI, and I keep thinking “Oh so that is KUNCI”.

And for example, now we have a few new members working with us. Acong came after me. And then after Acong there are others. Well they are interns and work on programs. But I am looking from a distance wondering if they are going to join us for good or are they going to go after the projects are finished. So it’s also the transmissions of awareness of being a collective or being together in time and space.

Binna: Many organisations we talked to responded on the question about membership that there is no formal procedure. It’s all based on “hanging out”. And then in the case of the artist Jompet Kuswidananto, they found out by reading an interview with him that he had said that he was part of Teater Garasi, which they were surprised about, as they didn’t consider him as a member. I wonder whether KUNCI can tell us a negative case, because I know you have a history of having other members who have left, besides personal reasons, inevitable personal reasons, are there other cases?

Dina: Do you remember I joined KUNCI with one other person?

Antariksa: Dimas! Oh yes, we tried having this kind of formal regeneration so we did a series of interviews with people and it was even worse actually, they left the organisation within six months, not even a year. So we decided that wasn’t a good way to have new members.

Binna: For me I had exactly the same experience. Interviews and open calls rarely work.

Antariksa: And even when a member left KUNCI, it was never really official. So they just disappeared little by little. They came to the office once a month, then next once a year, and then suddenly disappeared, but we still have actually friendship and relationships with them, and we also always ask them to come to KUNCI. So we have sort of common ground, you are no longer an official part of KUNCI for example.

Christine Wagner: Do you have an aim to grow? Or is it like you have to sustain the people to do the work? I there an interest in growing actually?

Dina: Growing the number of people?

Antariksa: We never really think about that. Well sometimes we need more people.

Ferdi: We always need more people. Because there is always more demands than we can meet, but it’s always quite pragmatic in the beginning, and if people decided to stay, then of course we will welcome them but it’s really open. A lot of these commissions, or demands, are project-based and involve salaries, but then when the project ends and we said “Hey, we can no longer pay you, if you want to continue to hang out here we would be very pleased, but if you want to go elsewhere and come back here again when there is a project, that’s also fine.”

Dina: In my case I actually want to have more KUNCI members, because I need someone to buy toilet paper.

Raquel Ormella: You need more KUNCI members like you!

Dina: Well actually one of the changes in the arts and cultural landscape in Yogya is that it is becoming more and more professionalised and the professionalism can overturn friendship, it is becoming more competitive. Like what professionals do, such as “This curator will meet me, but not meet you”. But this kind of competition can also make you feel quite excluded or lonely, so [I keep thinking] who is my ally and who can I work with? The nature of friendship is also changing among most cultural practitioners in Yogya, so I think in a sense, for me to have more KUNCI members is to have more allies, but I am also not just looking for registered members of KUNCI, I also am looking for comrades––ooh that also sounds very war-like––but I’m looking for more friends and colleagues in these arts and culture fields to work together, so not just at KUNCI but partners, or types of cooperation, not membership, but a working network perhaps.

Binna: A certain looseness has been possible it seems because the living costs are very low here. So you also compare to the Jakarta arts scene, for example, where living cost is much high, that’s why they are more ‘professionalised’ and that’s why ruangrupa had this division and that division. But it’s coming here as well right?

Dina: Yes.

Hans (Knegtmans): And that’s one of the risks when you’re growing.

Binna: And when the city is growing.

Hans: Even the organisation gets bigger with more partners, more comrades, then you wall compartments as well. That’s the risk.

Antariksa: The problem is this growing system is becoming more and more oppressive. They push us to do things that sometimes we don’t want to do. So the challenge for growing organisations I think is how to make them not only survive but also to make them unique and to maintain their own principles. That’s why the notion of sustainability of ideas was really interesting. How do we deal with this?

Emily: I would like to ask about the sustainability of a political position. Most of the organisations we met with talked about this moment in 1998, and about building networks around shared activism, and how after the fall of a dictatorship suddenly there was a moment when you could set up organisations. A lot of the organisations we met are trying to understand where they are now through looking at the past, after all of these shifts and turbulent times, where a lot of things changed and were redefined, and people were redefining themselves. How do you locate yourself in relation to this now? What is the consciousness of the organisation now?

Binna: Hafiz said the enemy became horizontalised. So house, family, media all became their enemies, and before their enemy was the Suharto regime. That’s why they started Forum Lenteng, focusing on alternative media.

Emily: In the UK London is being taken over by corporate interests to the point at which it’s hard to continue small projects that are carving a small space for something else. The public sector is shrinking, and the dominant culture is that of spectacle. We work a lot within our neighbourhood, collaborating and entering into conversations with local residents, through which we have been able to read the political on a micro-scale.

I see this here at KUNCI through what you’re doing in the kampong or the other kinds of research happening here. When we were talking, you skirted away from having to define it. In a way KUNCI can be defined by the different things that you do, but when you look at the library you and see this in the different sections of discourse––feminism, post-colonial discourses, European philosophy––you can see how you’re maintaining a complex position of intersecting discourses.

Ferdi: I’m always referring back to the individual aspirations that we project to the collective. For me it’s about working against normativity, and that actually allows us to go to different directions. Right now, for instance, people talk a lot about collaboration or relational art and it’s increasingly becoming a new norm in valuing art, and then for us it’s to actually find a niche, to position ourselves as a counter balance to these new social norms. The only word that we can pull out of these experiences is ”criticality”, but of course criticality itself is a bit overrated. Critique for its own sake have never really been our interest, but for us to be able to articulate how normativity works, so that we can see our own positioning in the discourse, either we speculate for it or against it.

But again, this is still my individual projection on the collective. Of course or Antariksa or Dina would have a different perspective, and these collective perspectives are perhaps what define us. At the same time, not all interests could directly translate into a common ground. So that is why if I don’t see it fit to KUNCI’s I do it elsewhere, like in the Researchers’ Affects Project. Not all of our individual interests are accommodated by the collective, I think it is important to accept that.

Binna: I wonder whether there are common causes shared among organisations or in an organisation in Indonesia though. As Emily said, all the organisation we met talked about 1998, which is not a long ago. It seems to be quite particular for the Indonesian art scene.

Antariksa: Yes, of course there is. I believe there is a common cause but I want to bring this idea in, well maybe its very Indonesian, or very Yogya, but from my point of view is it possible to understand KUNCI for example, for myself through the idea of family? Family doesn’t really need a common cause. They just happen like that. You’re my brother, you’re my sister, you’re my mother and you’re my father and we don’t really need a common cause. We cannot really express it how it’s possible, it’s really difficult but somehow things happen and we work together for different reasons and I feel like KUNCI is kind of my extended family.

Ferdi: Awww…

Antariksa: If you see it in this way… and sometimes you need to escape from your own family. So of course we have these values that you can position in the political history of Indonesia especially because we were founded just after 1998 amidst this freedom and of course we are against certain values such as censorship. But it could be difficult to formulate our values in a very solid form. It’s really difficult.

Binna: Why?

Antariksa: I feel like I have a second home so the place that you can stay and you can work and sleep––safely.

Dina: I agree with what Antariksa said about KUNCI being a safe space for everyone and about being a family and that we take care of each other but I think the forms of family do not eliminate the common cause but I was driven to this family because I have a common cause with the common causes of the rest of the family. So it’s an ideologically driven family. It’s not like this family with geese and that family with cats. But also maybe, and this might be coming from my position coming from an activist family, but my common cause moving into this field of arts and culture is to fight inequality. It sounds quite abstract and quite heroic in this time of chaos and crisis but I think this has driven me to move closer toward criticality. I am also interested in intellectual works as modes of thinking and doing in practice, not only just in theory but also in life, on a daily basis––for example in my attitude to local politics. In this way I feel I can move closer to KUNCI as my family or my safe house from the places I feel rejected from.

Brigitta Isabella (or Gita): I would actually prefer to call KUNCI a gang rather than a family.

Wok: Woah, so tough!

Gita: I was also interested to talk about membership and I was thinking to myself if it is possible to be an ex-member of KUNCI? I thought even if I have a different vision to what KUNCI is doing now, as Ferdi also said, you can also accommodate it outside of KUNCI whilst still investing something in KUNCI as well. You don’t see KUNCI as a working place anymore but a place that you invest things and for that, for me, you cannot be an ex-member as long as you have a shared vision. Unless of course you did something really bad and someone kicked you out of KUNCI. Everyone always says that we have a very informal bond and I think that’s what makes this unstructured structure stronger because of that rather than from making more solid and committed stuff.

Regarding to the diverse interest, I also see it that way. Like Ferdi has his own research on queer issues, Antariksa has his own interest in history research and I have my own interest in philosophy and I think what also makes us stronger is we have so many different perspectives and we can accept more jobs!

Sometimes I don’t do some of KUNCI’s projects because I’m abroad or I’m engaged in other projects but you are still a member of the team although you don’t really work. For example, Nuning (Nuraini Juliastuti is KUNCI’s co-founding member) has been doing her PhD for four years but there is always emotional engagement with the whole vision of the organisation.

Dina: This formula is very specific to KUNCI but its also not proven to be successful yet. For example we still find it hard to decide who will buy toilet tissue.

Gita: OK Dina, I’ll buy the toilet paper. I’m sorry! (Laugh)